I’m working on some materials for a CLE presentation entitled Remedies in Fiduciary Litigation. I’ll be giving it October 18, 2017 at the Lancaster Bar Association. Its also on the program for PBI’s Estate Law Institute in Philadelphia on November 14-15, 2017. Most of the equitable remedies available to beneficiaries whose interests have been harmed by an executor or trustee date back hundreds of years to the common law in England. But they don’t really do the job today. They are not adequate remedies. Here is an example:

I’m working on some materials for a CLE presentation entitled Remedies in Fiduciary Litigation. I’ll be giving it October 18, 2017 at the Lancaster Bar Association. Its also on the program for PBI’s Estate Law Institute in Philadelphia on November 14-15, 2017. Most of the equitable remedies available to beneficiaries whose interests have been harmed by an executor or trustee date back hundreds of years to the common law in England. But they don’t really do the job today. They are not adequate remedies. Here is an example:

What can a beneficiary do if she things the executor of the estate is paying too much in legal fees and taking too big of a commission as executor? The problem is how to get that issue before a court. You will see that the deck is stacked against the objecting beneficiary. How does it work?

1. The executor must file an account for adjudication in order to get the matter before the court. There is no deadline for this. If it seems like it’s taking too long, and after being asked nicely the executor refuses, the beneficiary must go to court to compel an accounting. Unless the executor has a very good reason, usually the court will order him to file an account, in maybe three months.

2. One hopes the executor would file the account in the allotted three months. He may ask for an extension. He may just not file the account. In which case, back to court the beneficiary must go to have him held in contempt. (Remember all these trips to court require an attorney and legal fees, paid personally by the beneficiary.)

3. OK. We get an account filed for adjudication. Now the beneficiary, through her attorney, must enter objections to the accounting. This is a legal pleading and it is a "once and done" opportunity. The objections have to cover everything. If you forget something, or don’t mention it in the objections, you lose your rights to pursue it,

4. Next the executor, through his attorney, (who he is not paying personally but who is being paid out of the estate which further reduces what the beneficiary will get, right?) will answer the objections, presumably denying everything and saying he did no wrong.

5. Now the parties must prepare for litigation in earnest. They will seek discovery, that is production on both sides of relevant documents, records, and statements on which the accounting is based. Perhaps there will be depositions of the executor and others involved in the estate. There may be motions. It may be necessary for the beneficiary to hire an expert witness in order to prove that the executor breached his fiduciary duty. Again, the beneficiary is paying out of her own pocket for all of this,

6. Eventually, if the matter can’t be settled, it will be schedule for hearing – after months or years.

7. In the meantime, while all this is going on, the executor is holding all of the estate’s assets and has made no distribution. And he doesn’t have to. The executor is entitled to hold distributions until the approval of his account. That means the beneficiary can go for years, getting nothing from the state, and personally funding this litigation.

8. At the hearing thee will be testimony about what the executor did, what the attorney did, what is usual and customary to be received as compensation for each, citation of cases, and in many instances a duel of exert witnesses, one for the beneficiary saying the fees are excessive and one for the executor saying that they are not.

9. Time passes and then the judge will issue an-ruling and hopefully an opinion. In my experience, it is rare for fees to be significantly reduced. They may be chipped away at a bit, but tit is not very likely that they will be reduced enough to begin to cover the beneficiary’s attorneys fees

10. So is that beneficiary’s remedy adequate? I say ‘no.’

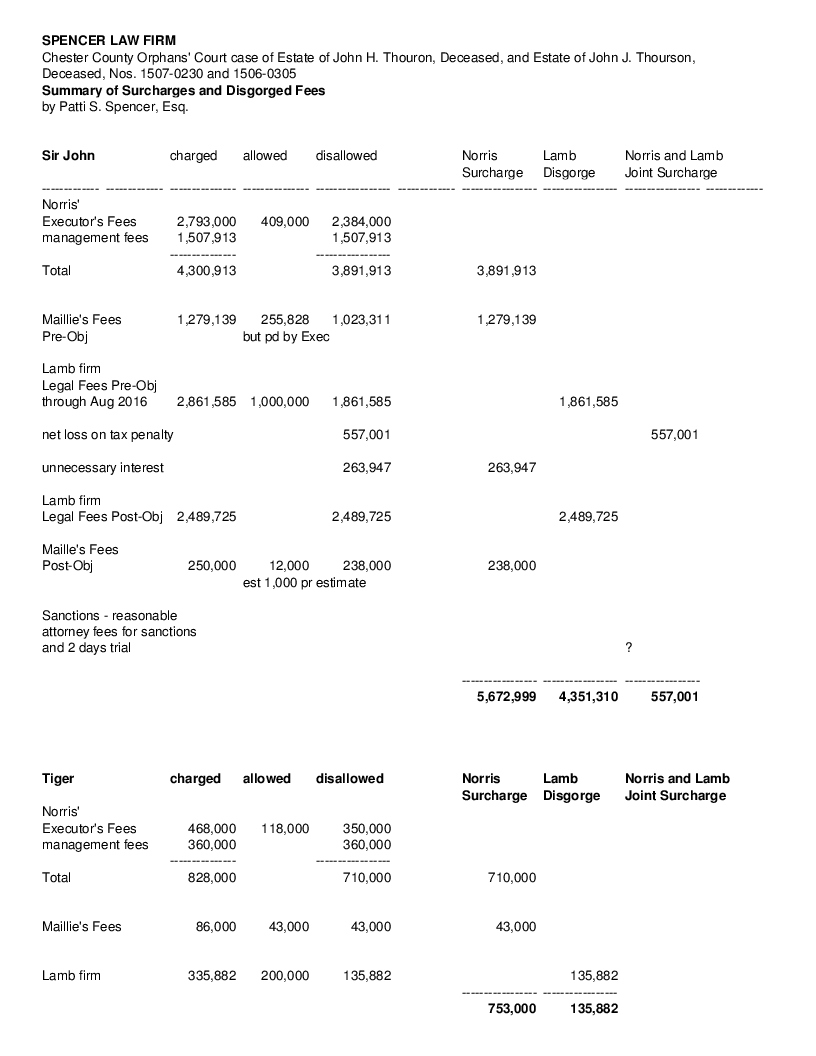

This blockbuster Adjudication, written by Judge Mark L. Tunnell is 212 pages long, and deals with many issues, but very significantly, with the issue of the appropriateness of attorney, accountant and executor’s fees. Judge Tunnell’s opinion is very thorough, very organized and very compelling. Unfortunately it is too long to be printed in the Fiduciary Reporter. But

This blockbuster Adjudication, written by Judge Mark L. Tunnell is 212 pages long, and deals with many issues, but very significantly, with the issue of the appropriateness of attorney, accountant and executor’s fees. Judge Tunnell’s opinion is very thorough, very organized and very compelling. Unfortunately it is too long to be printed in the Fiduciary Reporter. But

Estate of Powell v. Commissioner

Estate of Powell v. Commissioner If you’re spending your childrens’ money, you are probably breaking the law.

If you’re spending your childrens’ money, you are probably breaking the law.  The Supreme Court of Delaware, on appeal from the Court of Chancery has emphatically upheld spendthrift protection in trusts in the case of Mennen v. Fiduciary Trust International of Delaware. The Chancery Court opinion can be found

The Supreme Court of Delaware, on appeal from the Court of Chancery has emphatically upheld spendthrift protection in trusts in the case of Mennen v. Fiduciary Trust International of Delaware. The Chancery Court opinion can be found A Power of Attorney is a very important and useful tool. It is often used in elder care so that the named agent can manage the finances of the principal. While the agent under a power of attorney can do many things, some things are prohibited. For example, an agent under a power of attorney cannot make a will for the principal. Can the agent make a trust?

A Power of Attorney is a very important and useful tool. It is often used in elder care so that the named agent can manage the finances of the principal. While the agent under a power of attorney can do many things, some things are prohibited. For example, an agent under a power of attorney cannot make a will for the principal. Can the agent make a trust? According to the

According to the